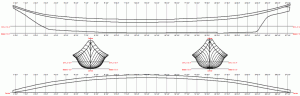

![Vietnamese Sampan from Hue area (line drawing) Vietnamese Sampan from Hue area (line drawing)]() |

| A sampan from the Hue area, probably much like those discussed here. Source: Junk Blue Book*. (Click any image to enlarge) |

The romanticization of traditional lifestyles is an insidious form of prejudice, one that leads to assumptions no less false and potentially no less damaging than racial prejudice. There's an assumption of something pure and right in traditional folkways that is lost when such ways are abandoned for modern/Western ways. It's little different from the old "noble savage" meme, which we've largely rejected in name, but which remains a strong theme in Western culture in the form of romanticizing supposedly more "peaceful" lifestyles that are "more in tune with the natural world," (in spite of the constant states of warfare that have been observed in many tribal cultures; in spite of smallpox, frequent childbirth deaths, illiteracy, et al, as being quite natural), and uncritically accepting, idealizing, ancient-and/or-Eastern "wisdom" that is often unwise in the sense that it is unsupported by science and often demonstrably untrue and harmful.

I acknowledge myself among such offenders – after all, Indigenous Boats is my blog, created and written because of my fascination with and appreciation for the boats and boating-related activities and peoples of non-Western – and especially, preindustrial (or should I say nonindustrial?) – cultures. I certainly can't shake the notion that there's something attractive about traditional, preindustrial folkways – in spite of the fact that, when given the chance, most preindustrial people eagerly adopt many, if not most, of the ways and material benefits of Western/industrial culture.

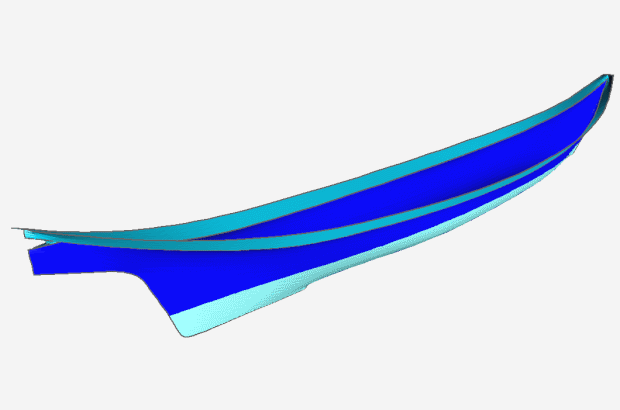

![Vietnamese Sampan from Hue area, photo Vietnamese Sampan from Hue area, photo]() |

| Hue area sampan (type HUBC-1a in the Junk Blue Book) |

So the sampan dwellers of Tam Giang Lagoon, in central coastal Vietnam, are a good object lesson about the relative attractions, to those directly affected by the choice, of a natural, traditional, or "primitive" lifestyle versus a modern, commercially-based one.

![map of Tam Giang Lagoon map of Tam Giang Lagoon]() |

| Tam Giang Lagoon (Source: DaCosta and Turner*) |

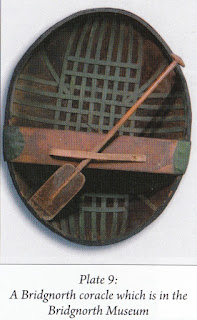

Tam Giang Lagoon, near the city of Hue, is the largest lagoon in Southeast Asia – about 70 km long, fed by a number of rivers, and with two narrow openings to the South China Sea. Historically, it was home to highly productive fisheries of many species, and as recently as 1985, some 100,000 individuals lived there year-round on about 10,000 sampans, one family per boat. If I have correctly identified in the Junk Blue Book* the type of boat in use there in the early 1960s, these boats were rigged with lugsails, ranged in length from 22 to 46 feet, in beam from 4.3 to 6.5 feet, and typically had a laden draft of just 1.6 feet. Today, almost all are powered by inboard engines.

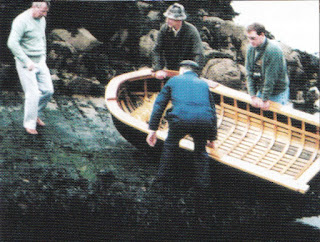

![A van of Sampans in Tam Giang Lagoon A van of Sampans in Tam Giang Lagoon]() |

| A van of sampans in Tam Giang Lagoon (DaCosta and Turner) |

Sampan dwellers were mobile fishers, relying on hook-and-rod and dip-net gear for a mainly subsistence living, with surplus catch being sold, usually direct to the consumer, in local markets around the lagoon. Groups of thirty to fifty sampans, their families often related, would travel together to fish different areas of the lagoon and gather near one another in floating communities called vans.

This was hardly the idyllic life that it might appear. Although the origins of the sampan dwellers are disputed, it seems clear that they were refugees from other parts of Vietnam, who took to the water because there was no farmland available in the region. DaCosta and Turner* describe them as "marginalized," and state that "The sampan dwellers tend to have low incomes, are landless, lack accessibility to government services such as health and formal education, and have poor living conditions." Furthermore, "They are scorned by land-living…society in general, who consider them…poor and uneducated. In turn, the sampan dwellers consider themselves isolated…." The sampan life even had serious spiritual drawbacks, because "Being landless…means, among other things, that families cannot bury their dead in permanent burial grounds, considered essential in Vietnamese society to ensure a successful after-life." Although I speculate, this philosophical weakness of their lifestyle might have had a negative psychological impact on sampan dwellers continually worried about life after death.

Prior to and during the Second Indochina War (i.e., "the" Vietnam War, to Americans), land-dwellers around the lagoon began staking claims in the lagoon by constructing fixed-gear fishing installations such as fish traps, weirs, and corrals and permanent dip-nets. Although these installations had no legal sanction, they proliferated, excluding the legally- and socially-impotent sampan dwellers from areas of the lagoon. Following the war, these permanent installations expanded rapidly, with aquaculture facilities added to the mix.

Eventually, privately-owned fixed-gear facilities covered such large areas of the lagoon that open fishery areas became severely restricted. The density of aquaculture operations also had negative effects on water quality and on the natural flow of water through the lagoon, further reducing the wild catch (and causing health and productivity problems for aquaculturists as well).

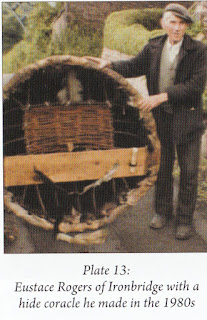

![net enclosures and small sampan, Tam Giang Lagoon net enclosures and small sampan, Tam Giang Lagoon]() |

| The lagoon's fixed fishing facilities and aquaculture pounds are largely tended with small sampans propelled through the shallow waters with a pole. (Source: Truong Van Tuyen, et al) |

After a typhoon in 1985 killed 600 around the lagoon – including many sampan dwellers – the Vietnamese government embarked on a program to resettle sampan dwellers to the land. The goals of the program were not only to reduce their vulnerability to natural disasters, but also to integrate them into the larger society and raise their standard of living. Entirely new villages were established solely for former sampan dwellers. Land was allocated to families, and partial funding provided for the construction of permanent homes.

These policies were far from ideal in their implementation. The land allocated was often marginal for agriculture, and the provision of credit for home construction was often inadequate and subject to political favoritism.

Nonetheless, some 90 percent of sampan dwellers came ashore, enticed by the chance to become landowners. Former sampan dwellers began establishing their own fixed-gear fishing and aquaculture facilities, farming terrestrially, and engaging in a variety of other land-based enterprises, while some of them also maintained their sampans for mobile fishing during the season when their time was not taken up by land-based agriculture. The former sampan dwellers were encouraged to join social and economic organizations and, as landed citizens, attained political and social parity in these groups and in society at large. They played a role, for example, in negotiated efforts to rationalize the location, size, and spacing of fixed-gear fishing and aquaculture installations. These efforts achieved success in improving flushing and water quality in the lagoon and establishing a fairer allocation of sunken lands both for landed citizens and remaining sampan dwellers.

Although DaCosta and Turner found significant disparities among the former sampan dwellers in the success of their adaptation to land-based living, they are, by almost any objective measure, generally better off than previously. They are now integrated into state educational and healthcare systems, are active in the larger economy, and, especially, are accepted into Vietnamese cultural life. In the words of one former sampan dweller:

"In general, I feel my life is much easier since I have been on land. Life on the boat is isolated. Now I have more friends, and my kids can go to school, and it is much easier for me to make a living… I feel that I have stronger ties with the members of the village than on the boat."

Another former sampan dweller reported that he had, in the authors' words, more "free time…to spend with his friends and neighbours. This allowed him to build stronger ties with other village members and, in turn, to gain information to aid his livelihood development." Those stronger ties included the pooling of resources among former sampan dwellers to finance the construction of individually-owned fixed-gear fishing and aquaculture installations -- something they might have done previously, had not their isolation discouraged such cooperation.

There's something sad in the loss of a traditional way of life – but that sadness seems to be mainly for those not living it. It is true that that loss was forced upon the sampan dwellers by external changes – especially by their exclusion from formerly accessible areas of the lagoon by the growth of privately-owned fixed-gear fishing and aquaculture installations. But to ask that the sampan dwellers be "allowed" to retain their traditional lifestyle unchanged by the modern world is essentially to ask that the modern world stop changing – and this is obviously a vain request. In the case of the sampan dwellers, their lot was made easier by humane government policies designed to incorporate them into the larger society rather than to marginalize them further. And that may be the best outcome to hope for for many traditional societies that will, in the future, be placed under pressure by inevitable changes in the modern societies that surround them.

*Sources

G. Levasseur, J.M. Lamperin, H. Le Neel, L. Chambaud, The Sampan Dwellers of the Vi Da District (Hue, 1993). Results of a survey preliminary to humanitarian aid intervention, 1994