Born in 1877 or thereabouts, Te Rangi Hīroa, aka Sir Peter Henry Buck, was a half-English, half-Maori anthropologist who studied Maori and other Pacific cultures. In his 1930 publication Samoan Material Culture (complete text here free), he described seven boat types of Samoa: three based on dugout technology, and four of sewn-plank construction. Quoting directly from the source, these were:

Due to the incursion of Western technologies and political administration, only one of each category was still in use during his research: the paopao and the va'a alo, although a few stray examples of some of the other types were still in existence, if no longer usable. Here we'll look at the paopao; we may address some of the other types in future posts.

Dugout Canoes

1. Paopao. The smallest dugout, with two outrigger booms, propelled by paddling.

2. Soatau. A medium dugout, with three outrigger booms, propelled by paddling.

3. 'Iatolima. The largest of the dugouts, with five outrigger booms, topsides, bow and stern covers, and sail.

Plank Canoes

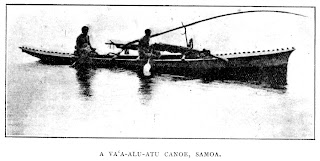

4. Va'a alo. The bonito boat made of lashed planks, with two outrigger booms connected with float, propelled by paddling.

5. Amatasi. A plank canoe larger than the bonito boat, with two outrigger booms connected with the float, a platform over the booms, balancing spars on the right, and a mast for sailing.

6. Taumualua. A wide plank canoe without outrigger, modelled originally on whaleboat lines, idea foreign but technique native.

7. 'Alia. The double voyaging canoe made of planks and consisting of two canoes lashed together.

1. Paopao. The smallest dugout, with two outrigger booms, propelled by paddling.

2. Soatau. A medium dugout, with three outrigger booms, propelled by paddling.

3. 'Iatolima. The largest of the dugouts, with five outrigger booms, topsides, bow and stern covers, and sail.

Plank Canoes

4. Va'a alo. The bonito boat made of lashed planks, with two outrigger booms connected with float, propelled by paddling.

5. Amatasi. A plank canoe larger than the bonito boat, with two outrigger booms connected with the float, a platform over the booms, balancing spars on the right, and a mast for sailing.

6. Taumualua. A wide plank canoe without outrigger, modelled originally on whaleboat lines, idea foreign but technique native.

7. 'Alia. The double voyaging canoe made of planks and consisting of two canoes lashed together.

Due to the incursion of Western technologies and political administration, only one of each category was still in use during his research: the paopao and the va'a alo, although a few stray examples of some of the other types were still in existence, if no longer usable. Here we'll look at the paopao; we may address some of the other types in future posts.

|

| Model of a paopao. All images from Samoan Material Culture. (Click any image to enlarge.) |

The paopao, or small canoe, was a single-outrigger paddle-propelled dugout designed for one man, although it was capable of carrying two in a pinch. It was used exclusively inside the islands' surrounding reefs primarily for transportation and for fishing, often by trolling a hook. According to Te Rangi Hīroa, the paopao was "in active general use throughout the (Samoan islands)…and is an indispensible part of every male adult's equipment in life." To quote further:

The paopao canoes are made by the householders who are not expert carpenters. A master builder while enumerating the canoes made by the carpenters' guild omitted the paopao. On my mentioning it, he smiled and said, "The paopao is not a canoe." Neither is it from the expert point of view. In the eyes of the guild they rank with the cooking houses and are beneath their dignity to build.

In Hīroa's time, most or all of this home-grown boatbuilding was done with steel adzes.

|

| Paopao in plan and cross-section. |

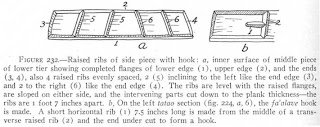

The main hull of the paopaohas a fascinating cross-section. The stem was heavy and vertical on the outside, and the hold was deepest at its forward end, gradually becoming shallower until it reached the rear outrigger boom, at which point the bottom sloped up sharply to meet the sheerline. The paddler sat aft of amidships, so his weight raised the forward end and this resulted in approximately even draft along the boat's length, but it also meant little freeboard aft. The knob at the very end of the stern was used as a fastening point for a rope when transporting the log from the forest to the boat's building site. It served no further function, but was retained as a decorative element.

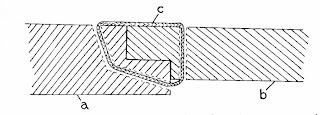

In plan view, the hull was narrow, double-ended, and roughly symmetrical fore and aft. Amidships, the hull was round in cross-section – i.e., it was not expanded – so the greatest beam was some inches below the sheerline. (A 16'8" LOA paopao hull measured 14.5" maximum beam.) Inwales were carved to provide a wider bearing surface for the outrigger booms: as they weren't intended to contribute to stiffness, these inboard hull flanges did not continue into the ends.

As the boats were not sailed, outrigger booms were fairly short: a measured 15-footer had booms 4'6" and 4'7" long. Each boom was lashed to the hull through a single hole bored just below the inwale. The booms were straight, and connected to the float by struts. The floats were long and pointed at the forward end, but cut off square just behind the aft support. Floats were aligned parallel with the main hull.

Because of the sloping run of the hull's bottom, the forward connecting struts were longer than the aft struts. Two styles of struts were observed:

1. Paired rods: Each boom had two pairs or ironwood rods, with the top ends lashed directly to the boom. The upper ends of the paired rods that were inboard of the float slanted inboard (i.e., toward the hull), while the rods outboard of the float sloped outboard. The bottom ends of the rods were sharpened and forced into holes bored on either side of the centerline on the top surface of the float. To make all fast, lashings were passed over the boom and through holes bored transversely through a longitudinal ridge standing proud on the upper surface of the float.

2. Forked branches: Each boom had a Y-shaped connector: the two upper arms of the Y were lashed to the boom, and the sharpened bottom end was inserted into a hole bored on the float's upper surface. The lashing method was not recorded, but it may have been similar to that used for the other method.

|

| Paopao end decorations |

Some paopao had decorative protrusions left standing proud on the upper surfaces of the solid ends. Short sections of V-shaped serrations were also carved into the gunwales of some of the canoes just inboard of the solid ends. The seat was a simple plank that locked over the gunwale just forward of the aft outrigger boom, and it was removed when the boat was not in use. Where paopao were used for rod fishing, a forked rod rest would be lashed to the forward boom, while the pole's butt end rested on the after boom.

(All information derived from Samoan Material Culture by Peter H. Buck, a.k.a., Te Rangi Hīroa)

.jpg)

by Claidhbh O Gibne. (Please don't ask me to pronounce the author's first name.) The comment worth a read, or you can see Wade's complete review on

by Claidhbh O Gibne. (Please don't ask me to pronounce the author's first name.) The comment worth a read, or you can see Wade's complete review on

, A.C. Haddon and James Hornell.)

, A.C. Haddon and James Hornell.)

by Ralph Diaz:

by Ralph Diaz:

.

.

, by Claidhgh (I understand it's pronounced "Clive") O' Gibne has received quite positive reviews. (Here's

, by Claidhgh (I understand it's pronounced "Clive") O' Gibne has received quite positive reviews. (Here's